Last Thursday the Interior Department announced that it’s removing Yellowstone-area grizzly bears from the endangered species list. It’s expected that grizzlies in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem (NCDE) will be de-listed in 2020.

For the first time in a lifetime, grizzly bears in the NCDE have been roaming far east of the Rocky Mountains following drainages, streams and food into the tan waves of farmland stretching out from the forest edges of the Rocky Mountain Front.

In the town of Valier, where about 500 people live along a lake an hour and a half drive from the mountains to the west, the community is still adjusting to living among grizzlies.

“We can’t grow the town. Our elementary school has a sign that says beware of bears. If I had elementary school children, would I want to send them to that school? Probably not.”

This is Ray Bukoveckas, the mayor of Valier. He told a group of state and federal wildlife managers visiting the town last week that people are afraid to let their kids wander around town like they used to, or to go on walks after dark.

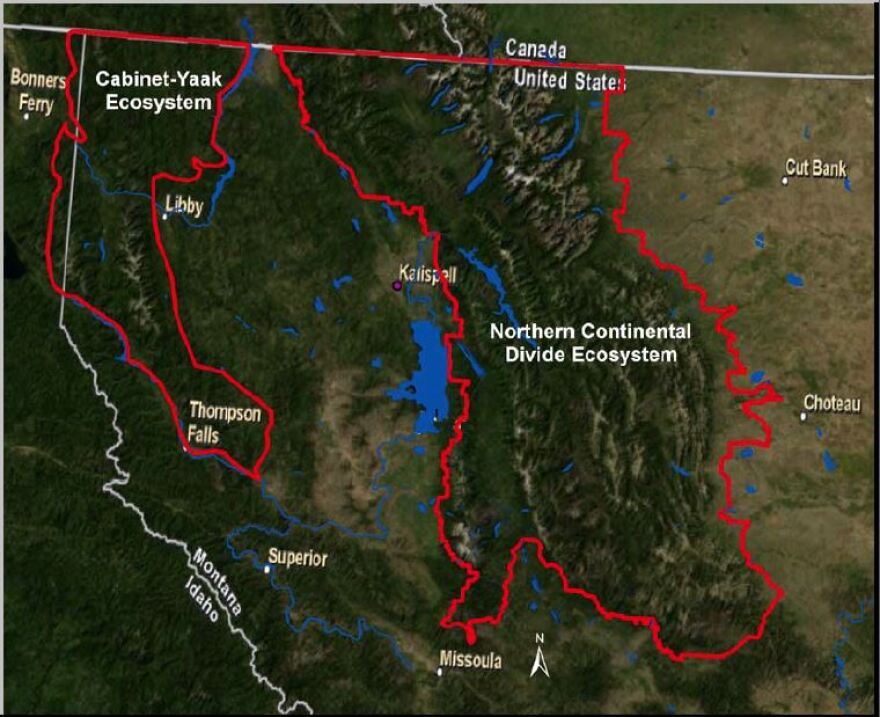

Valier was among a series of stops for the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) during a day long tour to learn more about human-bear conflicts in the Norther Continental Divide Ecosystem, which includes Glacier National Park, the Flathead, the Blackfeet Indian Reservation and the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

The IGBC is almost done with a five year plan to guide the future of grizzly management, and a big part of that is coming up with ways to reduce human-bear conflict.

In Valier, Mayor Bukoveckas told me that means setting up a what the town is calling a bear patrol.

“If they get a call that there's a bear in town, they will go out," he says. "If it’s at night they have searchlights on their pickups. They use the search lights to make the bear aware that we know you're there, and the bear don’t like that. They're trying to show the bear that you need to be out of town.”

Bukoveckas says the city council also decided to cut down some of the bushes next the to the lake along the town, to make it easier for people to see bears. But he says some people weren’t happy about that because it was destroying wildlife habitat.

“Well I’m sorry, I think the people are more important than bears. That’s the way it is,” Bukoveckas says.

Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks bear biologist Mike Madel is in charge of preventing or at least minimizing human-bear conflicts in this area. He’s been on the job for a couple decades, and since he started his position he says he’s having to cover up to three times the area he used to, responding to bear sightings and conflicts:

“It’s an enormous area. So we’ve been stretched really thin," Madel says. "We try to respond within 24 hours to every conflict, but sometimes that’s even difficult to do. They would like to see someone there within an hour and it’s difficult to do.”

Property owners in the area have complained about the slow response time by FWP, and it’s gotten to the point where some people have stopped reporting bear sightings at all, even if the bear is right next to a town. That lack of communication concerns some people who live in towns next to the mountains and wonder about the future management of the bears.

Madel says FWP is almost done with the hiring process to bring another bear specialist into the area to help with conflicts.

Ali Newkirk lives along Dupuyer Creek, in the town Dupuyer, about halfway between Valier and the Rocky Mountains. She keeps chickens and lambs, with a small orchard of plum and apple trees. Newkirk lives next to the home she grew up in.

“Well, when I was a kid we didn’t have bears in the area, so we’d play in the brush, we ran, and did whatever we wanted to do," Newkirk says. "We didn’t even think about bears. Occasionally, one of the folks who lived way up toward the mountains would maybe kill a bear and you’d hear the fact that that happened. It was a different time and mindset then.”

A few years ago, two of Newkirk’s sheep were killed by a grizzly. When that happened, the local Fish Wildlife and Parks officer asked Newkirk if she wanted the bear destroyed. She said no.

"You know, it’s a dilemma for me. No, I don’t want to just kill all the bears. But I don’t want them killing all my stuff either, my animals, my friends, my pets," says Newkirk.

A few months after the sheep were killed, she did what a lot property owners around the area are starting to do, she installed an electric fence. It wasn’t something she wanted to do at first, when local wildlife managers, including Mike Madel, asked her about the idea. Newkrik didn’t see why she had to fence herself in, while the bears got to do whatever they wanted.

But she eventually agreed. She hasn’t had any bear problems since, although she still needs to carry bear spray when she goes on walks outside her gate in the evening.

Mike Madel with the Montana FWP says it’s going to take a lot of outreach and education to teach people about how to live among grizzly bears.

“It's the issue of the unknown. That unknown generates fear. I hear a lot of that fear. It’s an issue that, as bears reach out further and further,we’re going to have to deal with that," Madel says.

Last week the U.S. Interior Department announced the removal of endangered species list protections for the grizzly bear living in the Yellowstone ecosystem. Wildlife officials are planning on de-listing grizzly bears living in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem by 2020.

“We’re ready to move forward on that,” Madel confirms.

Madel says the number of bears living in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem has grown from about 380 bears in the mid 1970s, when grizzlies were put on the endangered species list, to more than 1,000 now.

Once the bears are de-listed, most of the management and monitoring of the bears will shift from federal to state and tribal hands. This could allow hunting seasons of the bear, which some people, like Valier Mayor Ray Bukoveckas think will help teach bears that it’s not a good idea to be around humans.