As we reported yesterday, this winter may be warmer and drier than normal in Montana. Experts base their predictions on El Niño, that band of warmer-than-normal ocean water in the Equatorial Pacific. Exactly how dry and warm could it be? That's tough to pin down, but history provides some guidance. The El Niño of 1997/'98 was the strongest yet recorded.

Bob Nester is a senior forecaster with the National Weather Service in Missoula. Nester says average sea surface temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific then were about 2-degrees Celsius above normal.

"The forecast for us is to be anywhere from 2 to 2.5 degrees (Celsius) above normal. What that translates to is one of the strongest El Niño's experienced since we've been keeping records dating 50 to 100 years ago."

If the forecast holds up, that could pack a wallop.

"Statistically for example in Missoula, anytime we've had a moderate to strong El Niño, snowfall has been anywhere from 75 percent of normal or less. Each time."

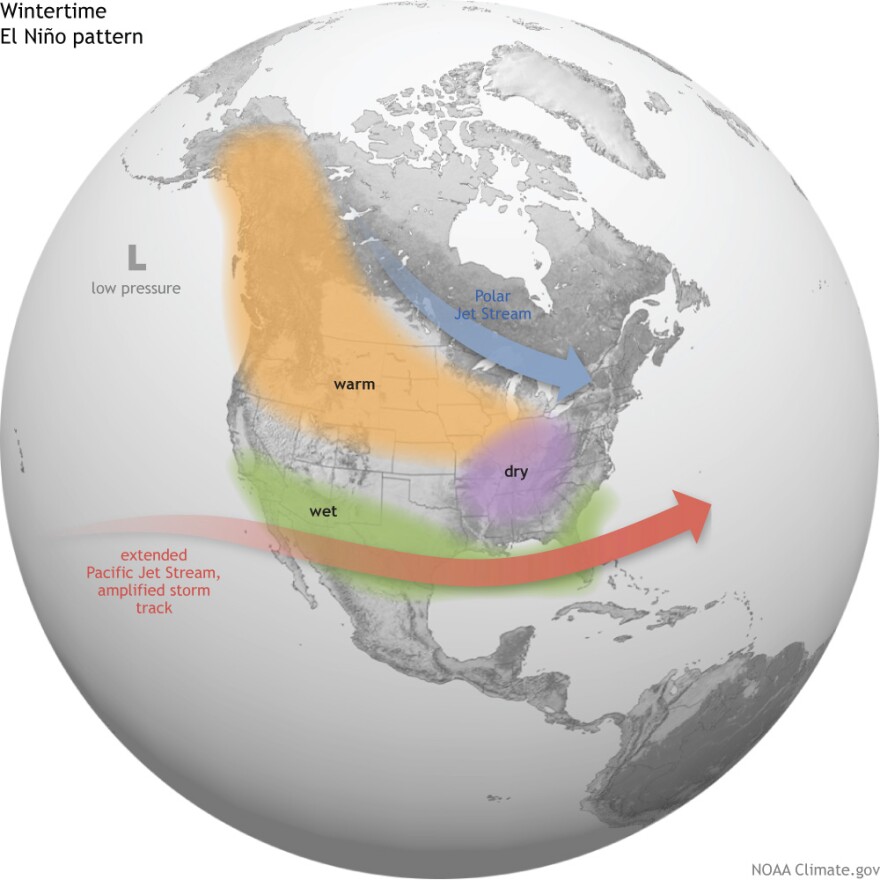

El Niño years also always lead to snowpack that's 75 to 90 percent below normal across Montana. So how does the same El Niño that’s expected to bring badly needed and perhaps devastating rain to California simultaneously shut the tap off here in Montana?

"When El Niño happen on a general large scale the main jet stream impacts the southern part of the U.S. more than it does up here. They get more precipitation, on average, down in California and the southern tier through Florida. Where that leaves the northern Rockies or western Montana is, in general, a ridging pattern."

Nester, who also serves as a fire incident meteorologist, says the prediction of a warmer and drier winter doesn’t automatically doom Montana to a difficult fire season next year.

”Wildfire season is all about potential. If you have potentially a wet spring that might close the window on how long your fire season might be. I want to stress that El Niño has the most impacts just in the winter season. There’s not a lot of correlation as to what might happen for El Niño in the spring seasons. We have had above-normal precipitation after El Niños in the spring.”

Nester adds that while the climate has been warming over the past couple of hundred years, a possible El Niño-related mild and dry winter in the Northern Rockies would not be considered as a symptom of global climate change.

"No. Climate changes on the order of decades and centuries. Weather is day-to-day or season-to-season – that’s weather. Climate’s a whole different ballgame. To take a particular event, a severe event, and correlate it to climate change is just not scientifically correct.”

This video from NOAA explains how El Niño works:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Tuou_QcgxI